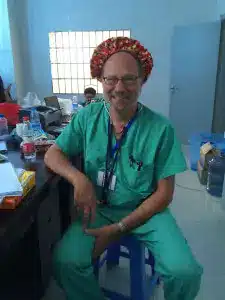

Just like this summer’s hit movie, Dr. Anton’s recent Operation Smile mission was full of adventure, fun, and challenges. As some of Dr. Anton’s patients know, he was recently involved with a mission to Wenshan, China located in the southern Yunnan province. This was his fifth mission since first meeting Operation Smile founders Dr. William and Kathy Magee in 1989 while completing his Facial Fellowship in Virginia.

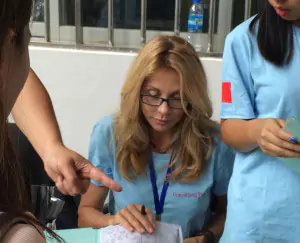

Wenshan proved to be a blockbuster mission for Op Smile as 161 children with cleft lip and palate received free corrective surgery. I luckily happened to be one of the 75 volunteers on the mission. My official job was Medical Records. This is one of the few positions that is non-medical. My unofficial title was the self-appointed keeper of the stories of everyone connected to the mission. I hoped to be like the camera, taking in bits of light through a lens and creating a lasting image.

Every mission is different. The location, the team, and the patients all contribute to creating the essence of how the story will be told and remembered. Any time you bring 75 strangers for one week to live like a very large extended family, there will be stories. Most of the volunteers were Operation Smile veterans. Henry, a pediatric cardiologist from New York, has been on over 30 missions. Angela, a flight nurse from Colorado, spent three weeks in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. Diana, an ER nurse from Virginia, goes on two to three missions each year. Sharon, aka, “the blister” is semi-retired but still makes time for yearly missions. It makes you wonder, what it is that makes the heart of a volunteer tick?

Every Mission Tells a Story

Wenshan was by all accounts an incredibly successful mission. Surgery records were broken and new ones set. It was a very important mission for Operation Smile (not that they all aren’t important), but this was the first mission for Op Smile in China since forming a new alliance with the China Charities Foundation for Children.

Wenshan was also an incredibly demanding mission. Just getting there was a feat. This is to be expected when your final destination is halfway around the world. What was not expected was Typhoon Chan-hom, the largest in decades to hit Shanghai where our flight was headed. Typhoon rain or shine every volunteer had to arrive in Kunming by 8:30 am July 14th to catch the bus for the eight-hour ride to Wenshan. For many of the volunteers it took two full days of zig-zag travel to get there—three if you count the day chasing the sun across the Pacific Ocean.

By the time our bus pulled into Wenshan the team had begun to bond. A good friend of Dr. Anton’s that he met in Haiti concluded that a mission is a kind of social sifter, meaning it tends to draw together people of similar interest and purpose. Lives that might not otherwise intersect are suddenly traveling along the same path for a common good. There are no hidden agendas. No politics. No hierarchies. Doctors, nurses, and non-medical professionals treat one another with equal importance. They know it truly is a team effort to move 161 people through the surgery process and safely back home again.

Exhaustion was commonplace and contagious.

Our days were long, sometimes 15 hours and counting. Mornings began with a 6:00 am wake up call. There was the official call from the hotel receptionist or the unofficial alarm of the rooster in a nearby yard. Breakfast was nothing more than an excuse for a mandatory team meeting before boarding the bus to head to the hospital. Team meetings were akin to a bi-lingual pep rally since few of us shared a common language. They were meant to amp us up for the day, which was necessary since there wasn’t a strong Espresso on hand to do the job. Team meetings were also meant to ground us in the reality of our responsibilities.

Henry repeated the same mantra every morning at breakfast. “Safety, safety, safety,” as though these were the three wishes he would like granted. It’s hard to imagine the enormous undertaking of moving supplies and personnel into temporary operating rooms in countries thousands of miles away. Add to that a language barrier that created a communication gap as deep and as wide as the Grand Canyon.

There is not a lot of common ground between English and Mandarin Chinese. This becomes very evident when asking for a simple bottle of water turns into a game of charades. There is no room for games in the operating room, however, and thanks to the team translators, like Ada Rong who assisted Dr. Anton; we were able to walk the tightrope across the Grand Canyon safely to the other side.

Of course, not everything always goes as planned, like not having tape for the IVs. This doesn’t seem like much of a problem until forty or fifty crying babies try pulling them out of their hands. Not having a properly functioning defibrillator was another major issue and delayed the start of surgery the first day by many hours. Then there were the smaller inconveniences like no toilet paper…anywhere…in any of the bathrooms…in the entire hospital. Diana was kind enough to share her stash with me, and the secret toilet she discovered in the nurse’s lounge that wasn’t a “squatty potty”.

Every Volunteer Tells A Story

It is a powerful experience to stand united behind a cause you so faithfully believe in. Still, each volunteer had his or her own reason for being there. Paula, a plucky thirty-something from Canada, loves the adventure. She turned a personal life crisis into a one-year mission in India. Paula wears such an intoxicating ear-to-ear grin that it seems whatever needed healing in her was accomplished through her commitment to helping others. Many of the volunteers echo the same sentiments, “You get back what you give.”

Volunteers give a lot on these missions. There are sacrifices when you decide to upend you real life to support the Wenshan mission. For some, like Jen the Child Life Specialist who cares for her infirmed mother, it was time away from family–and the six rescue dogs she adopted. You didn’t have to know Jen for long to feel her heart because she offers it to everyone she meets. Her job was simple, play with the kids before they went in to surgery. Simple? Have you ever tried to comfort a terrified toddler who is surrounded by strangers wearing masks and funny-looking paper hats? Jen did it with toys, hugs and song. We could hear her sweet voice echoing the words to, “You Are My Sunshine,” throughout the hospital.

Then there were all our wonderful Chinese volunteers, many of whom served as translators. They were mostly young and (mostly) tireless. If I could ask them for one gift to take home with me, it would be their work ethic. These were some of the most dedicated workers I’d ever met. Not a hint of the sense of entitlement that cripples generations from reaching their highest potential and happiness. If I could have left one gift it would be some of our American light-heartedness that comes from knowing your life is more free than bound.

Every Patient Tells A Story

More than 200 hundred patients plus their families traveled to Wenshan in hopes of receiving surgery. They gathered outside the hospital waiting for the team to arrive. Arrive we did, like the cavalry. We stormed the hospital and set up camp in nine different stations. Patient’s traveled along a course of registration, imaging, and vitals before making their way to the plastic surgeons to determine if they are a candidate for surgery.

Families came from local farms and from hundreds of miles away. Many wore the traditional clothing of their villages while others were dressed in their finest threads that were mostly threadbare. There were grandparents, uncles and aunts standing in for parents who could not leave work. Most of the patients were infants and toddlers but a few were adults who had lived with the stigma of cleft lip and/or palate their entire life. It was not hard to see how such a condition effects one’s self esteem. These patients were shy to make eye contact and covered their smile behind their hands when engaging.

Even parents of children born with cleft lip can suffer. Sometimes the family is outcast as people, even family members, often don’t understand cleft or apply meaning to it that is built on cultural superstitions. The parents of one of Dr. Anton’s patients shared that his daughter, who was one of seven grandchildren, was never held or played with by her grandfather because her cleft lip scared him. The little girl’s mother expressed to Dr. Anton that he made her daughter “more beautiful” so that she can be “a part of the family now”.

These were the stories with happy endings. But there were other stories with unresolved endings, like the widower whose nine-month old son got sick the day of surgery. This was the man’s second trip to Wenshan; the first time his son was too young. The boy had been abandoned in the streets when he was but a few days old, presumably because he was born with a bilateral (both sides) cleft lip. The father wept being told his son would have to wait again until the next mission.

The good news is there will be many other missions to Wenshan and the other 44 countries Operation Smile visits. The organization is committed to treating every eligible surgery candidate across the globe. Perhaps it is Op Smile’s dedication that draws only the most committed volunteers to its cause. The kind of people that will work tirelessly just to see a child smile.

In the end there wasn’t one reason for the 75 volunteers from 16 different nations to come together. There were 161 reasons. When we look back we won’t remember the hard parts: exhaustion, eating the same Chinese food for breakfast, lunch and dinner, typhoons, jet lag, and those squatty potties. We will remember the look on a mother’s face as she sees her child right after surgery. We will know that our efforts changed someone’s life for the good, including our own.